Dana Denis-Smith

CEO, Obelisk Support

Foreword

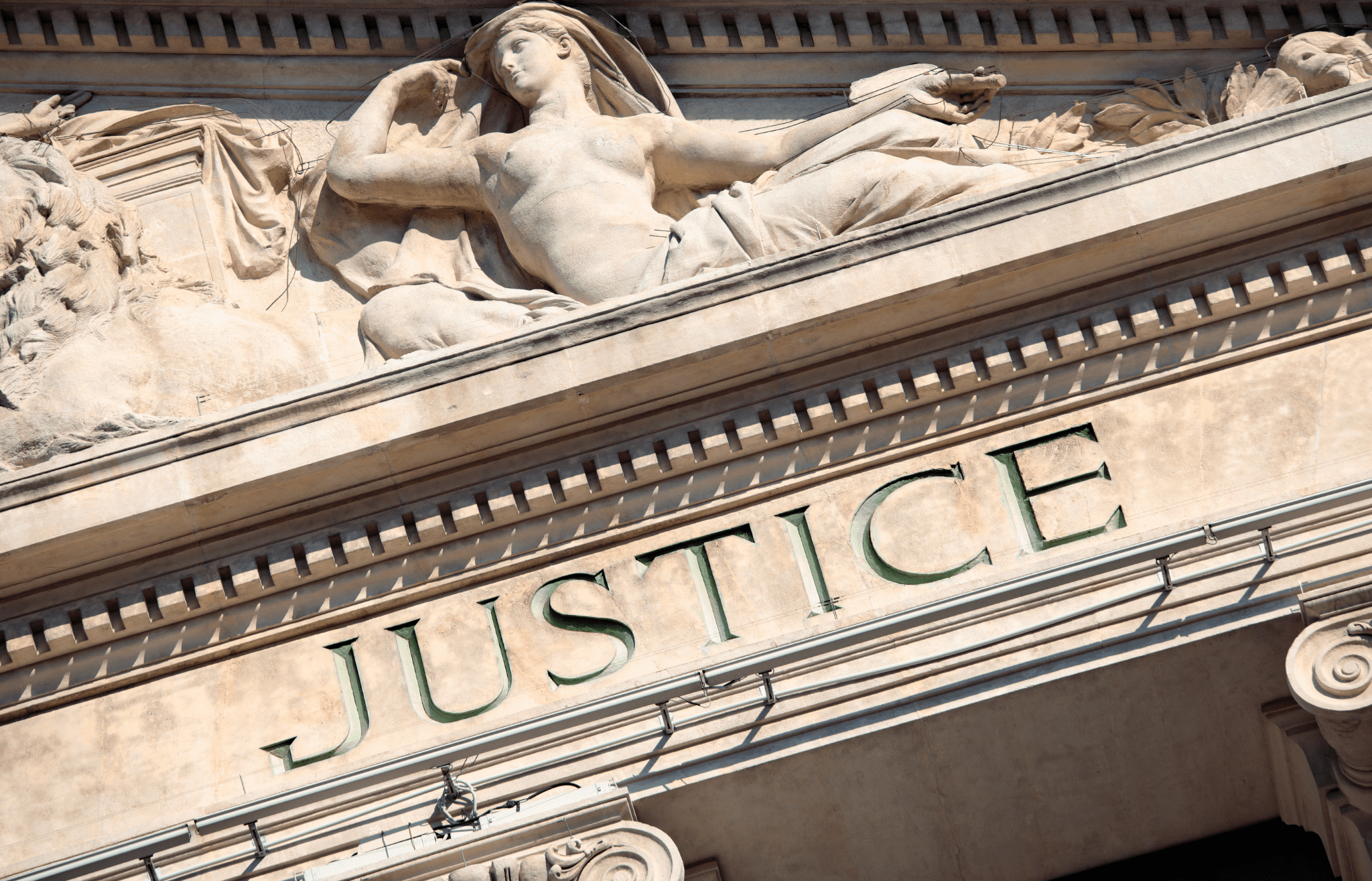

People, environment and purpose – is it time to recast our legal ecosystem along these values?

I am delighted that Obelisk Support’s latest report – World in Motion: why the legal profession cannot stand still’ – is tackling this head-on and sets out to investigate how the next generation of lawyers is expecting the legal profession to shift to a business model that prioritises sustainability beyond profitability. We see the new legal system being supported by four key pillars that will help drive the change the profession needs to see: purpose and profit; environment; access to the profession; and ethics.

Having been one of the key strands to come out of our 2022 Legal Reset culture report, ethics returns this year, and we explore further its importance for the new generation of students, trainees, associates and in-house counsel. Aided by a fascinating roundtable we held, this report investigates culture more closely taking into account the voices – and expectations – of tomorrow’s legal leaders.

Legal sector organisations and in-house legal team seeking to attract and retain talented employees cannot simply up junior lawyers pay.

They need to consider the values of the organization and its purpose. That means implementing diversity initiatives, considering environmental and sustainability credentials, and looking at the suppliers they use. For law firms and other legal services providers, it means considering which clients they are prepared to act for and the pro-bono work they undertake.

This needs to be contextualised as part of the wider debate that has sprung up especially in the last year about the profession’s ethics. Last year, the Legal Services Board – the oversight regulator for the profession – expressed concerns about the ethics of in-house and commercial lawyers in particular, citing a host of topical issues, including: the role of lawyers in the Post Office scandal, governance failures at the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors for which a City law firm was in part blamed, the contentious use of nondisclosure agreements in employment disputes, the leaked Pandora and Panama papers, SLAPPs(strategic lawsuits against public participation),and weaknesses in sanctions and anti-money laundering compliance.

The next generation is clear in its assessment that the legal profession cannot avoid moving with the times and needs to evolve to match a changing world. As society shifts away from the one-eyed pursuit of profit, it must be underpinned by the law.

The next generation is aligned to this need to balance profit and purpose – an overwhelming number of respondents to our survey of junior lawyers (86%) conducted for this report showed that they are looking to effect positive change in society through their work as a lawyer.

A legal profession that matches these new priorities of purpose, equality and environmental awareness needs to be at the heart of this. And the legal businesses that reflect this will be the trusted partners of their clients.

“The next generation of lawyers is expecting the legal profession to shift to a business model that prioritises sustainability beyond profitability.”

DANA DENIS-SMITH

CEO of Obelisk Support

Introduction

Is the pushback against profits per equity partner(PEP) finally starting? And does it have something to do with another acronym rapidly gaining ground in the City – ESG?

This stands for environmental, social and governance, a set of standards measuring a business’s impact on society, the environment, and how transparent and accountable it is.

The fixation on profits per equity partner as the definitive measure of law firm success has long ruled the City legal landscape but this year’s results season has witnessed the first cracks in its supremacy. Mishcon de Reya decided that it would no longer disclose PEP, describing the metrics as ‘unhelpful’, CMS revealed its turnover but not profit, while Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer announced that, from next year, disclosure would be limited to the mandatory accounts filed several months after the year-end.

While law firms are businesses like any other and look to maximise profits, these moves suggest that there is a growing realisation that there are alternative ways to measure success.

ESG issues are increasingly on the lips of clients, staff and partners; it is no longer enough just to pump up salaries (although that obviously remains crucial) – law firms have to show that they are good businesses, as well as successful ones.

As with most things, more focus on sustainability in the round represents both an opportunity for law firms – ESG is a thriving new practice area for many – and a threat, as they have to show their own credentials both to clients and staff. A survey conducted in 2021 by the Law Firm Sustainability Network in the US found that 87% of responding law firms had received requests for proposals that included the firm’s environmental efforts.

Indeed, in 2023 BT Group renewed Addleshaw Goddard’s place on its legal panel because of the firm’s commitment to driving diversity and inclusion across all areas of its organisation. Microsoft’s longstanding law firm diversity program offers law firms a bonus of up to 3% of their annual fees if they meet the diversity targets set by the technology behemoth.

In this report, we will look at how sustainability has become a vital focus of the modern law firm and hear from junior lawyers working in law firms and in-house about the progress the legal profession is making in terms of its culture and ethics. What is really important to them? What are their priorities, and are those at the top of the profession listening? Who are the trailblazers leading the way and what can other firms and corporate teams learn from them?

With special thanks to our contributors

DISCUSSIONS WITH:

Matthew Hill

CEO

Legal Services Board

Lubna Shuja

Immediate Past President (2022-23)

The Law Society of England and Wales

ROUNDTABLE PARTICIPANTS:

Oliver Bridal

Legal Counsel

Citeline (Norstella)

Olivia Brooks

Associate

Bates Wells

Alfie Cranmer

Regulatory Associate Solicitor

Kingsley Napley LLP

Priya Dasani

Associate

Stephenson Harwood LLP

Grace Kendrick

Solicitor

CMS

Holly Moore

In-house Advisor – Brand Protection

ITV

Lara Oseni

Legal Officer and Case Presenter

General Pharmaceutical Council

Abigail Pidgen

In-house Solicitor

Arup

Hollie Rhodes

Former Contracts Manager

Obelisk Support

Anna Vroobel

Associate Solicitor

Irwin Mitchell

“It’s the future leaders who may well have a different approach to life and to work and to what’s important to them”

MATTHEW HILL

CEO of The Legal Services Board

A Changing Generation

We have reflected in our previous culture reports on how the new generation of young lawyers have different expectations of their legal careers and employers than older generations.

Deloitte’s annual global survey of Gen Z and Millennials found in 2023 that satisfaction with work/life balance and employer progress on DEI, societal impact and environmental sustainability have improved. But the majority remain unimpressed with businesses’ societal impact overall. Less than half believe business is having a positive impact on society at a time when they have high expectations for their employers and for businesses overall. “They continue to believe that business leaders have a significant role to play when it comes to addressing social and environmental issues,” the survey said.

In law firms, lawyers rank work-life balance as the most important attribute of their workplace

Future Ready Lawyer survey, Wolters Kluwer

The Wolters Kluwer Future Ready Lawyer Survey from last year identified slightly differing priorities among private practice and in-house lawyers. In law firms, lawyers rank work-life balance as the most important attribute of their workplace, followed by career development/faster promotion opportunities– it is the other way round for in-house.

Being a purpose-driven organisation and having a diverse and inclusive culture are bottom of the list, in ninth and tenth, for private practice lawyers, but higher (fifth and seventh respectively) for their in-house counterparts, who also happen to be their clients. Strikingly, employers are generally not delivering what their staff want, the survey found.

But plenty of individuals buck this trend. One of our roundtable participants, Abigail Pidgen, is a good example.

She qualified at a US firm and, while it was an “amazing grounding” for her career, “I did always have this nagging feeling – was I part of something that was trying to shape a better world?” So she went in-house at engineering consultancy firm Arup (tagline: Shape a better world).

While it’s a big, multinational business, “at our very core is the value of sustainable development”, Abigail explains, “so we’re a very principles- and values-driven business”. This was a “huge driver for making the switch”.

%

of junior lawyers say they are looking to effect positive change in society through their work as a lawyer.

Our survey of young lawyers backs this up. Nearly three-quarters agree or strongly agree that they would not join an organisation whose values did not match with their own, even if they were offering more money. Saying that, only 58% are actually working at an organisation whose values match their own.

An even higher proportion (86%) say they are looking to effect positive change in society through their work as a lawyer.

FROM SELF-REPORTING TO INTENTIONAL BUSINESS CONDUCT

According to the Corporate Governance Institute, ESG as we know it today was first referenced in 2004 report from the United Nations entitled Who Cares Wins. The 18 leading global financial institutions that endorsed the report were “convinced that in a more globalised, interconnected and competitive world, the way that environmental, social and corporate governance issues are managed is part of companies’ overall management quality needed to compete successfully”.

It continued: “Companies that perform better with regard to these issues can increase shareholder value by, for example, properly managing risks, anticipating regulatory action or accessing new markets, while at the same time contributing to the sustainable development of the societies in which they operate. Moreover, these issues can have a strong impact on reputation and brands, an increasingly important part of company value.

“This summary holds true today as law firms have moved to ESG from corporate social responsibility(CSR). While superficially these may look identical is more about self-reporting and accountability, while ESG is a business practice that sets out specific goals with quantifiable results.

Data hub KnowESG says: “Establishing and controlling fiscally relevant environmental, social and governance risks and opportunities is an essential component of ESG strategy. This process separates ESG from CSR by focusing the disclosed operations or business model. In comparison, CSR may reflect values held within the company itself, but ESG reporting focuses solely on materiality in order to identify potential areas for improvement.

“Another way of looking at it, and an approach that should resonate with law firms, is that ESG is a risk management strategy. “Smart legal practitioners will see ESG as an opportunity to manage risk and drive positive change, both for their clients and their own firms,” Nicole DeNamur, a US lawyer turned ESG consultant, wrote last year.

With virtually every major company now issuing some sort of sustainability report, law firms as suppliers are under pressure from clients to be part of the solution, especially on environmental issues, with contractual requirements becoming increasingly common.

As Larry Fink, chairman and CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest investment firm, has put it: “Every company and every industry will be transformed by the transition to a net-zero world. The question is, will you lead or will you be led? “

“Smart legal practitioners will see ESG as an opportunity to manage risk and drive positive change, both for their clients and their own firms”

– Nicole DeNamur

A Herbert Smith Freehills report in 2021 that interviewed 20 GCs at major international companies found ESG at the very top of their agendas and considered strategically critical to their organisation. These GCs were increasingly likely to have been given significant responsibility for oversight and leadership on ESG issues too.

Only

%

Of junior lawyers are working at an organisation whose values match their own.

Ms DeNamur wrote: “Law firms that are early adopters of tracking and accurately reporting their emissions (and other key ESG metrics), will have a real market advantage.

With all these tools and resources available, the question for law firm leadership then becomes, ‘what are you waiting for?’ Failing to take action in this space also raises ethical considerations.

”ESG has in part developed out of concern that some businesses were using CSR as a PR exercise; ESG focuses on actual activities and successes, and is increasingly becoming an integral part of corporate reporting.

Though there are no specific requirements on law firms to report their ESG activities, some are caught by wider obligations, such as statutory gender pay gap reporting, in place since 2017 for businesses with at least 250 employees. A 2021 Law Society analysis of the reporting of the 41 largest law firms found an average 20% discrepancy between salaried women and men based on hourly pay (the highest was 39%), far more than the national pay gap of 14%. The median gap was even higher, at 32%. Statutory reporting may well in time be extended to ethnic pay gaps too.

What are lawyers there for?

AN INTERVIEW WITH MATTHEW HILL, CEO, LEGAL SERVICES BOARD

In preparing the report, we enjoyed a discussion with Matthew Hill, chief executive of the Legal Services Board – the oversight regulator for the legal profession in England and Wales – to explore culture in the law taking into account the expectations of tomorrow’s leaders and how the legal profession must evolve to match a changing world.

Matthew says issues around ESG and ethics go to the heart of what it means to be a lawyer.

He explains: “What are lawyers there for? Is the legal profession just a means of making a living or does it have something more profound to it? In my view, lawyers play an absolutely key role in underpinning a safe and civilised modern democracy, and how lawyers go about their business has a major influence on public confidence.”

And yet, there is an undoubted perception – fuelled by things like the Post Office scandal, increased public awareness of the use of non-disclosure agreements to cover up misconduct in the workplace, and weaknesses in sanctions and anti money laundering compliance – that this role is not always front and centre for all legal professionals.”

Indeed, towards the ends of the spectrum of perception is a view held by some serious commentators that some legal professionals are willing to do just about anything to someone if the money’s right. Of course, everyone subject to legal proceedings is entitled to a legal defence. But there are documented concerns about the conduct of lawyers in cases where an imbalance of power leads to an unfair, detrimental outcome for someone or where individuals in vulnerable circumstances are exploited to benefit the other party.

“It’s the future leaders who may well have a different approach to life and to work and to what’s important to them. It seems to me critical for those nearer the start of their careers than the end to be involved in the conversation about what they want from their profession and – as you would expect me to say as a regulator – how they see regulation helping to achieve that.

“Remember, regulation is not just about rules and sanctions – it is about education, training, standards and so on, which together with strong professional leadership can help build a hugely positive sense of purpose.”

Matthew says climate change is a great example of this. While those in their 40s and beyond have had to come to terms with it, some more reluctantly than others, Millennials and Gen Z have lived with it their whole lives; it’s more central to who they are. “We’re seeing a new generation of potential leaders who have lived through a different part of history and are likely to have different priorities as a result. Focusing on issues of social justice and social conscience is normal for them. You might start seeing that expressed in how businesses are formed and run.”

He stresses that he’s not saying everyone has to go off to do criminal work or become eco-campaigners. It’s about understanding that being a lawyer comes with privileges and obligations. “By all means enjoy the privileges but society will demand the obligations. You’ll have to give up some of your rights – you won’t be able to say exactly what you want in public, or behave as you want, because what you say or do has an impact on public confidence.” This is a link that many lawyers do not make, he suggests.”

Understanding and indeed living this trade-off is perfectly compatible with a very successful and rewarding career. What it boils down to in the end is an overriding commitment to the law as a means of securing fair outcomes that recognise a broader public interest, while focusing closely on the best interests of the client. And it means eschewing any sense of the law – or rather the craft of the law – being used to harass, intimidate, silence, or otherwise get in the way of those fair outcomes.”

Understanding this makes regulation, if not redundant, then hopefully more of a back-up. “We want to harness what should be the great joy of being part of a profession in which the public places its trust. Instilling purpose, excitement and mission will take you a long way before you put a rule down on paper.

”On EDI, he says the plethora of outreach initiative is a recognition that there’s a problem to be solved and that efforts are being made to solve those problems but he’s concerned that their success seems rarely to be evaluated. “I know it is a provocative thing to say”, Matthew says, “but the current paucity of evaluation might in fact limit success to a sort of ‘feel good’ factor rather than addressing the real barriers to progress that many legal professionals from a range of backgrounds currently face. The solutions may well need to be more fundamental, more structural.”

He goes on: “I don’t think you can be properly pro-EDI and pro-status quo at the same time.

Existing business models have contributed to the current situation, which I think most leaders recognise is not where they want to be. So you might have to be prepared to flex those business models and associated custom and practice if you want to make progress.”

Take work allocation. “We have absolutely no way of knowing if there are imbalances in the way work is allocated, because there is almost no data publicly available. Hypothetically, if you had to publish data every year, for example, about the value of work allocated by protected characteristics, you may start getting some insight. This is different to outreach. Outreach is all about changing the people to fit the system –I’m talking about changing the system to fit the people.”

Matthew also cautions against complacency that the demographics of law students today will automatically mean that the law is in a better place in 20 or 30 years. “It’s not a safe assumption that today’s entry level composition will be tomorrow’s partner composition. It might look a little more diverse but will still be skewed because of the profession’s structure.”

This is, he concludes, a “clarion call” to the profession. “What do you want to be known for? How do you want the public to see you? How do you want your members to deal with the weighty responsibilities put on them by the public having joined the profession?”

“While these descriptions of unethical behaviour clearly cannot be applied fairly across the professions as a whole, I don’t think it would be wise simply to dismiss them.”

It raises the question, he goes on, of whether “some form of course correction” might be needed, and this is a question that many senior lawyers are in fact asking of themselves, their employers and of their professions.

One problem, he suggests, is that “we find ourselves talking most of the time to the established leadership of the professions – the ones who have built their careers in the existing system. Cultural change is not easy, particularly when there is very little incentive, and it will disrupt the system for those benefiting from the status quo. So, understandably, not everyone is engaged in this debate or readily sees the need for change.

“It is difficult to imagine a workplace in which good ethics thrive unless there is also a healthy and supportive culture built on trust, openness and principled leadership.”

LUBNA SHUJA

Immediate Past President (2022-23), The Law Society of England and Wales

The Four Pillars

We see the new legal ecosystem being supported by four key pillars that will help drive the change the profession needs to see.

PURPOSE AND PROFIT

In some ways, lawyers’ jobs are inherently purposeful when looked at in the wider context of supporting access to justice and promoting the rule of law. But those principles may not always seem present when pulling an all-nighter on a complex banking transaction.

Environmental issues, aside from being apriority in and of themselves, are a good example of where purpose and profit can rub together, not always easily.

There is an increasing number of organisations in the law pressing for greater environmental commitments, such as General Counsel Sustainability Leaders (formerly Lawyers for NetZero), Legal Sustainability Alliance, Lawyers Are Responsible and the Chancery Lane Project. A significant moment came in April 2023, when the Law Society of England and Wales published groundbreaking guidance on the impact of climate change on solicitors.

It is particularly notable for accepting that climate-related issues may be valid considerations for law firms in deciding whether to act for potential clients. While the principle of access to justice and right to legal representation are “fundamental”, it says that solicitors are not “obliged to provide advice to every prospective client that seeks it” and had “wide discretion” in choosing whether to accept instructions.

The guidance says: “Some law firms are evaluating risks to their commitments in this area and some are placing limitations on the instructions they will accept citing their own organisation’s climate change commitments…

Turning away clients for ESG reasons is now ingrained at Bates Wells, the London law firm that was the first legal practice in the UK to become a B Corporation, a global movement that seeks to balance profit with purpose. Obelisk recently joined its ranks, just the 11th legal services business in the UK to do so.

Some solicitors may also choose to decline to advise on matters that are incompatible with the1.5°C goal, or for clients actively working against that goal if it conflicts with your values or your firm’s stated objectives.”

Olivia Brooks works in the corporate team at Bates Wells. She told the roundtable that B Corp certification motivates a lot of people to join the firm. “I can’t believe that I’m at a firm where we actively turn down work that does not align with our values,” she says. “I trained at a firm where, we didn’t have the privilege to say no to things. Whereas at Bates Wells, certain things are an absolute no-go, like oil and gas, but they go so much further than that.”

Becoming a B Corp goes way beyond signing a charter and issuing a press release.

It requires demonstrable change. Businesses must show” high social and environmental performance”, make a legal commitment by changing their corporate governance structure to be accountable to all stakeholders, not just shareholders, and exhibit transparency by allowing information about their performance measured against the standards to be publicly available.

Renowned for its testing nature, B Corp certification focuses on five areas of a business impact: governance, workers, community, environment and customers.

Obelisk Support founder Dana Denis-Smith stresses that B Corps do not deny the importance of profit. “They just say you have to make sure that profit is ‘good’ profit – that you’re not doing any harm as part of making it.” But she says professionals face a dilemma – are oil and gas companies, say, not entitled to representation? Many at the Bar hold the cab-rank rule tightly, for example.

In a letter to The Times earlier this year, responding to an editorial questioning lawyers acting for Russian oligarchs, Lord Pannick KC wrote: “The primary ethical obligation of lawyers is to the rule of law, which requires that all persons, however ‘dubious’, have access to legal advice and representation.

This applies to alleged murderers, rapists, paedophiles and also to Russians. There are exceptions to this professional obligation, and rightly so, in particular that we may not assist litigation which we believe to have no reasonable basis or which is being pursued to harass others.

But in general, judges, not lawyers, decide whether litigation by clients is well founded.”

And yet at the 2023 launch of the Institute of Business Ethics taskforce on business ethics and the legal profession – focused on City firms’ work for oligarchs and kleptocrats – chair Guy Beringer, former senior partner of Allen & Overy, argued: “In matters of criminal law, there is a well-established principle that all defendants should have a right of representation. In relation to commercial matters which have no criminal element, no such principle has been clearly established.”

At the roundtable, Oliver Bridal, who works in-house at Citeline, questions where the line gets drawn on not accepting certain types of work. “Presumably most of the companies that are doing green projects are the oil and gas companies, so do you say no to all of their work? Or yes to only some of it? But then if you say no to some because it’s oil and gas, they’re not going to give you other work. So where do you draw the line? And then do you say no to certain green projects that require rare Earth minerals? It’s very complicated.”

Fellow participant Grace Kendrick, an associate at CMS, says it is just as important to know your personal limits.

“Especially working in a big City firm, there are other people who could step up and do that work if you genuinely don’t feel comfortable doing it and your firm should want you to do the best you can.” She mentions a lifelong vegan she knows at another firm who was allowed to refuse to work for a fishing company.

While nearly two-thirds of those Obelisk surveyed say employers should allow them to refuse to work on certain matters for ethical reasons, only18% are able to say that their current employer does this. Just over half say they would feel able to challenge management if they believed they were being asked to do something they saw as unethical.

The Law Society guidance acknowledges that in-house lawyers may face particular additional challenges in advising on climate legal risks. “Asin-house lawyers cannot limit their advice to the scope of a retainer, they may need to be proactive in raising questions about the sustainability of business models and alignment to any climate pledges made by their organisations.”

Abigail Pidgen identifies who companies and firms are accountable to as an issue. A private company is ultimately accountable to its shareholders, “and you have to demonstrate profit and demonstrate to them that you’re driving profit”.

Arup is a trust owned firm with no individual shareholders or external investors. “This means our leadership have that extra level of freedom, like Bates Wells, to say: ‘We do want to work with these clients; we don’t want to work with those clients. We’re going to actively turn down work in this area or we are going to participate more in this area’, and it doesn’t have to be purely driven by profit and loss.

Law firms are generally owned by their partners and so they too have a lot of power to decide the direction they want to go in. It’s an interesting dynamic in our sector.”

ENVIRONMENT

These considerations flow into our second pillar. The Law Society guidance predicts that the interpretation of SRA principles in the context of climate change is “likely to evolve over time” and certainly the ethical pressure is starting to rise. In2022, an open letter organised by Plan B.Earth – a charity that supports strategic legal action against climate change – and the Good Law Project said lawyers should be ethically obliged to advise clients of the serious risks, legal or otherwise, of pursuing activities that risked exacerbating climate change.

The guidance says: “Some law firms are evaluating risks to their commitments in this area and some are placing limitations on the instructions they will accept citing their own organisation’s climate change commitments…

The pressure is slowly ratcheting up on big law firms. US organisation Law Students for Climate Accountability (LSCA) turned its attention to the UK this year and its report The Carbon Circle, the UK Legal Industry’s Ties to Fossil Fuel Companies, says large UK law firms play an “indispensable role” in supporting the fossil fuel industry.

It says fossil fuel projects worth “a gargantuan £1.48 trillion” were facilitated by a group of 55 large London law firms between 2018 and 2022, more than two and a half times the £546bn in renewable energy transactions they handled. LSCA encourages students to ask firms about their fossil fuel work and client selection processes, and recommends that associates assigned to fossil fuel clients should request to opt out of that work.

Our survey found that respondents evenly split over whether their employer is doing what it should be to address the challenges presented by climate change, while a quarter were not sure.

The group Lawyers Are Responsible has taken the LSCA findings on and begun standing outside magic circle firms on a weekly basis (the report said these five alone were responsible for over £285bn of work on fossil fuel transactions over the four years), handing out leaflets and engaging staff in conversation about the issue.

It has written to them, calling on them to phase out existing fossil fuel work. This might seem more than a longshot, but Slaughter and May, for one, has at least been prepared to engage in a dialogue.

Lawyers Are Responsible is a new type of campaign group in the law, one willing to take more direct action. It made a splash when it launched, after barrister signatories to its Declaration of Conscience pledged not to prosecute climate protestors or advise on fossil fuel projects, sparking a debate about the cab rank rule.

Grace Kendrick worked for six months in the Department of Business’s international climate finance team before training as a lawyer and recently qualifying into the energy and infrastructure team at CMS.

She works on renewable and clean energy and says there are “a lot of open conversations” in what was once called the oil and gas team. “It’s changing but it’s not going to be overnight.”

Plenty of lawyers may think their area of practice is unconnected with climate change.

Caroline May, sustainability partner at Norton Rose Fulbright and chair of the Law Society’s working group on climate change – which drafted the guidance –said last year that a lot of lawyers understood the importance of the issues the world is facing but may struggle to understand how it affects their daily practice.

In a Law Society Q&A, she went on: “However, I think on closer examination (and once you start demystifying the agenda), people quickly see how it is cross cutting and may impact their daily practice and that of their clients whether it be insurance risks, latent environmental liabilities, or public health issues such as air/water quality.”

The In-house Options

Advice from General Counsel Sustainability Leaders says in-house counsel need to communicate the legal and regulatory requirements that impact their organisation.

It quoted Vincent Brugge, GC of ICL Group and one of its champions, saying: “Sustainability was not part of a GC’s formal education but now legal and compliance play a significant role in tackling these sustainability challenges and educating themselves will be crucial.”

Second, GCs need to ensure there are “robust and meaningful governance structures” in their organisation so as to embed sustainability and ESG-led thinking and reporting. “An important aspect of the governance structure will be defining and incorporating tangible requirements, measurements and targets, and reporting against these to show progress made.”

Third, GCs must engage their boards and senior leaders – the tone is set from the top.

The advice went on: “In-house lawyers are in a unique position of influence and should engage with your senior management and boards to champion climate change actions and formulate strategy. This may be relatively easy for you, if senior leaders have already bought in, or you may need to be more persistent and continue championing this agenda.”

In a video for LexisNexis earlier this year, CatieSheret, General Counsel at Cambridge University Press & Assessment, said: “If you’re lucky enough to have permission to engage in this stuff, you could definitely be leading in it.” Even when in-house lawyers are not in a position to take a leadership position, they can still get involved in driving ESG policies for their organisation, such as by using the contract clauses devised by the Chancery Lane Project that work towards a decarbonised economy.

In-house lawyers should also focus on compliance, Ms Sheret went on: “You can encourage compliance teams to think about how they build consideration of environmental issues into due diligence [and] the kind of questions they ask third parties.”

ACCESSIBILTY

It is by no means just the ‘E’ of ESG that law firms and in-house teams need to respond to. The ‘S’ looms large as well in the forms of diversity, equality and inclusion (DEI) and wellbeing – these are essentially about how easy it is to access the legal profession.

The solicitors’ profession may have become majority female in 2017 but you would not know it by looking at its upper echelons. The most recent Law Society figures found that, while women made up 53% of practising solicitors in 2021, only18% of those in private practice were partners, compared to 39% of men, figures that have barely shifted in 15 years.

Those from Black, Asian and minority ethnic(BAME) backgrounds made up 18% of solicitors. A quarter of BAME solicitors were partners, compared to 35% of White counterparts; BAME solicitors were three times as likely to be sole practitioners.

These demographic trends will only accelerate–among those starting law degrees, women outnumbered men by more than two to one, while35% of students were from BAME backgrounds.

The proportion of solicitors working in-house grew to 25%, in line with the 1% annual increase seen for some time, although the Law Society said this was still a likely underestimate as some were not officially recorded as working in-house.

Social mobility has only been measured in recent years, in part due to the pressure of the Social Mobility Commission.

In 2016, it noted how privately educated people still dominated the legal profession, with barriers to entry for those from less affluent backgrounds even more acute at the bar than among solicitors.

This will take time to change – the most recent figures from the Solicitors Regulation Authority, for 2021, show that 22% of lawyers working at firms it regulates declared that they attended an independent/fee-paying school, compared to a national average of 7.5%.

According to an analysis last year by Law.com, the gap is significantly bigger in the City, with just 38% of partners and40% of lawyers at 68 firms (the top 50 plus large US firms) being state educated. Of the 23 firms that provided data about whether their lawyers attended Oxbridge, the average was 38%.

Of course, this is not just a legal sector issue. Research by the City of London Socio-Economic Diversity Taskforce last year found financial and professional services “deeply unrepresentative of the communities they serve”.

There are also significant issues with intersectionality. Research commissioned in 2020 by several leading City law firms from the Bridge Group, for example, showed that Black employees at the firms were much more likely to be from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

It found that solicitors from lower socio-economic backgrounds took around 18 months longer to reach partner than those from higher ones; being female and/or from a non-White background” amplify the inequalities in rates of progression”.

The Accountability Challenge

In relation to gender (focused on retention and advancement), and race and socio-economic background (focused more on recruitment in the first place), the profession is now awash with initiatives to improve opportunities. These include both broader business programmes, such as the Social Mobility Pledge and 10,000 Interns Foundation, and law-specific movements, like the Race Fairness Commitment and the Women in Law Pledge.

The question with all of these initiatives is accountability and we are slowly seeing more concrete commitments from law firms. National firm TLT, for example, has recently set a target of achieving 35% ethnic minority representation across early career roles (trainees and apprentices) by October 2030. Progress against the targets will be shared with the firm’s ethnic diversity network and supported by “robust investment from the firm both in terms of resource, finance and targeted initiatives”, including the creation of new advisory roles and additional senior and strategic roles within the business, and a new outreach programme aimed at schools and relevant partnerships.

In 2023, Slaughter and May said it was the first major law firm to set social mobility targets, backed by a comprehensive action plan.

By 2033, it said it aimed to increase the representation of lower socio-economic background individuals in the firm from a baseline of 19% to 25% – with the proportion of lawyers rising from 10% to 15% and business services population going from 35% to 40%.

The firm said it would publish its progress against its targets annually and also introduce voluntary reporting of social mobility related pay gaps as part of annual pay gap reporting.

An increasing number of large law firms in the UK are signing up to the Mansfield Rule, an annual certification scheme that started in the US and measures whether law firms have considered at least 30% women, racial and ethnic minorities, LGBTQ+ lawyers, and disabled lawyers for leadership and governance roles, equity partner promotions, formal client pitch opportunities and senior lateral positions.

An in-house version has now been launched for legal departments that requires 50% consideration of all historically under-represented lawyers for internal leadership and outside counsel roles.

The evidence indicates that this kind of targets based approach works. According to Diversity Lab, which awards the certification, the US firms that were early adopters after the Mansfield Rule’s launch in 2017 have diversified their executive committees and equity partnerships at statistically significantly faster rates than other firms.

For example, while non-Mansfield firms increased the racial and ethnic diversity of their management committees by a tenth of one percent, Mansfield firms increased by 4.4%.

Strikingly, while only 12% tracked the diversity of their leadership pipeline before signing up to the initiative, now 100% do so.

There are many pockets of smaller activity too. In2020, Amanda Callear, then senior legal counsel at Volkswagen, launched a paid legal internship for those who are under-represented in the law, working with national law firm Shoosmiths. She has since moved to Scania as general counsel but the programme continues, with this year’s cohort of four students experiencing life at all three businesses, and they receive lifelong mentorship from her too.

Motivated by DEI

Many of our roundtable participants were motivated by DEI issues. Anna Vroobel, a medical negligence solicitor at national firm Irwin Mitchell, sits on its DEI board and leads the disability diversity group. She says her involvement came from self-interest after becoming a disabled person post-qualification, which made her realise “quite how poorly the legal sector is set up to support people who are having additional challenges”.

She says: “Taking disability as an example, there are so many people who are barred from even actually getting training contracts – even work experience – because of others’ attitudes or literally not being able to get through the door.”

That is still a problem – earlier this year, the Bar Standards Board wrote to chief planning officers in central London to express concern at the difficulties chambers face in adapting historic buildings for disabled access.

Grace Kendrick worked multiple part-time jobs to fund her studies at Bristol University and, “having broken a barrier myself”, became involved with DEI initiatives there too, such as the 93% Club, for people who went to state schools, as well as at CMS, which has various diversity networks.

Shortly before the roundtable, she had co-organised the firm’s first mobility roadshow and she recounted how it led to two partners who had worked together for years discovering each had come from a social mobility background. “That for me was a big moment because I realised that it takes the young lawyers to move things forward,” Grace says. “We’re a new generation.”

She continues: “We talk about these things because we know it’s important, and the more you talk about it and share your experience, it can inspire those behind you and it can help them to break the barriers too, making a much more diverse workplace. One of the partners actually said, ‘I don’t know why it matters. I’m here now. No one judges me in my role as partner based on my background’. I said, ‘Well, it is important because you are inspiring everybody around you and also the future of your workplace too’.”

The idea that you can be what you see is critical for law firms. When looking to move, it was important for Olivia Brooks to feel that making partner as a female was a tangible goal at a prospective employer.

“It wasn’t in my previous team, where the partnership was majority older, male partners, whereas 50% of the partnership at Bates Wells is female and 35% work part-time. It feels very achievable because it’s something that I can physically see.”

Abigail Pidgen says her general counsel at Arup is a Black woman, while women head up various teams. “Senior leadership across the business is extremely diverse, so it’s not just that I entered a business that says it is driven by principles – I can actually see it. Being able to live that is really powerful and I appreciate it every day.”

Apprenticeship Breakthrough

The creation of solicitor apprenticeships, allowing school leavers to become solicitors without going to university, represents a gamechanger for social mobility. Their number, though still relatively small, is growing rapidly, albeit largely outside of the City. So it was significant earlier this year when the City of London Law Society launched the ‘City Century’ initiative, which has seen more than 50 member firms commit to taking on at least two solicitor apprentices by autumn 2024 and to then steadily increase their numbers. City Century envisages that, by 2040, at least 100 new partners will have been created by the solicitor apprentice route. This is a very modest ambition, in truth.

For Holly Moore, social mobility is at the core of her professional identity. She was state school educated and is a first-generation university student and professional from a non-traditional background, where a career as a solicitor seemed out of reach. The year she left college was when the first few solicitor apprenticeships were on offer. She had a successful application cycle and chose to start her career with producer and broadcaster ITV.

“It was the way it made me feel as soon as I walked in the door, seeing diversity in front of me– people from all different backgrounds, career changers, not traditional lawyers – that made me feel as though I belonged there,” she told the roundtable. As she progressed, “my passion for DEI came to the forefront because the more I got into the legal industry, the fewer people like me I saw”. I wanted to really make a difference by being open about my experience, encouraging others and using the apprenticeship as a tool for social mobility.”

A key reason is the importance of diversity of thought, Holly says. “Having different people from different backgrounds can only make an organisation stronger. Ten people in a room who all grew up the same and all think the same are never going to make progress. So it’s about helping people get through the door to places like that in the first place.” She qualified in 2022and joined ITV’s brand protection team as a legal advisor.

Getting your workplace in order

We have written in previous reports about the wellbeing problem facing the profession –LawCare’s 2021 Life in the Law report highlighted the need for the profession’s “organisational culture” to tackle the ongoing problems of mental ill-health, bullying and harassment. More recently, Law Society research said this year that solicitors score lower than the UK average on all positive measures of wellbeing, and are more likely to rate their anxiety higher.

Survey after survey this year has confirmed the problem. One commissioned by welltech company Frog Systems said law firms were not responding to employees’ need for support with mental health and wellbeing, seeing supporting staff morale as low on their list of priorities. Where support was offered, in the form of wellbeing advice and counselling, take-up was low, suggesting it did not always meet the needs of staff.

The SRA has updated its guidance on workplace environments in a bid to tackle law firms with an “unsupportive, bullying or toxic” cultures. It followed publication last year of a thematic review of workplace culture. While most solicitors the regulator spoke to said their firms had a positive workplace culture, 25% said they would be uncomfortable reporting “unacceptable behaviour concerns”.

There is now an explicit regulatory requirement on solicitors to treat colleagues “fairly and with respect”, while law firm managers must “challenge behaviour which does not meet this standard”.

Nonetheless, every law firm in the land will laud its culture and professional approach. The reality, of course, is sometimes very different. How genuine is the conversion to the issues discussed in this paper? For Holly Moore, it is not necessarily negative that some are doing it only because they have to. “At least they’re doing it and something is happening, and they might come around to thinking it’s really important. And, actually, just by doing it they’re inspiring people to do it with them. It’s not where we want to be but it’s progress.”

But the pace is frustrating young lawyers. Abigail Pidgen says: “I can see this young generation of lawyers coming through that really care about this, but unless people at the top now start really listening and changing things, it’s going to take us all 20 years to get to that level and actually start doing something. We haven’t got that time. We need to be doing it now.”

Shortly before the roundtable, a leading law firm had press released reaching its target of having women make up a third of its partnership two years early – nobody thought this was much to shout about, however. “I agree that it’s great that some firms recognise that this is a live issue and are doing what they feel they can to address it, but when we get to the stage where it’s like, ‘Look at me, I deserve a gold star for implementing change’– that in my view should be standard – it gives a sense that the actions taken to address the issues are performative,” Lara Oseni, a legal officer at the General Pharmaceutical Council, told the roundtable. “Yes, I agree it’s an improvement, but it doesn’t feel like such a massive shift when you consider that it is 2023. It just feels minimal.”

But isn’t this what the legal profession is like? She replies that the attitude of some senior lawyers is holding the profession back. She recounts the reaction to an article a colleague of hers wrote in a legal publication about mental health and the importance of work-life balance for junior lawyers.” The comments suggested that junior lawyers should just be grateful, that senior lawyers had to work under terrible working conditions, and if they did it, so should you. I think that mindset is so toxic, why can’t the mindset be ‘I worked under terrible working conditions so you don’t have to’?

Another example is how some firms allow partners to work remotely five days a week but expect juniors to be in the office every day.” Again, it’s a case of reinforcing this notion of unnecessary suffering/excessive monitoring when the pandemic has proved that most tasks can be performed at home. Why are some law firms afraid to adapt to a hybrid way of working?”

An associate told the roundtable. “There is something among the older generation where, either consciously or sub-consciously, they think, ‘I worked bloody hard to get into this profession and no one cared about my mental health. I worked long hours. Why should the younger generation get away with a nicer culture?’ Perhaps there is a bit of resentment there.”

Holly Moore says she hates hearing ‘I had to struggle so you do too’. “Why is it not, ‘I struggled so you don’t have to’?” she demands. “It’s going to be a struggle regardless. Law is a difficult profession. People have to work really hard but you shouldn’t have to work this hard just to get afoot in the door.”

A danger for those banging their heads against this wall, brick or otherwise, is burn-out, cautions Anna Vroobel. “There are trailblazers in each firm – junior lawyers banging the drum for DEI, for social responsibility – and if you’re coming up against a structure that isn’t making that change, be that because of bureaucracy or decisionmakers at the top not being receptive – there are only so many times you can send the emails, chair the meetings and try and get buy-in before you think, ‘You know what? I can’t do this anymore’.”

Some firms are addressing this head-on by allowing this work to count towards lawyers’ billable targets. As a member of the Irwin Mitchell’s DEI board, Anna Vroobel’s target has been reduced by 5% to give her time to dedicate to this work and it also forms part of her objectives.” I’m getting a lot of positive reinforcement and it’s a real marker of a firm that is valuing DEI,” she says.

Fellow roundtable participant Priya Dasani, a banking associate at City firm Stephenson Harwood, says it too recognises “productive“ hours – whether working on DEI or giving an internal training talk, for example – as counting towards her target.

This is also where new-model businesses such as Obelisk come in. A junior lawyer explains their very nature means they address these issues from a different perspective.

“They operate differently and have to set themselves apart with their offering. So they really buy into this to show that, from a cultural perspective, they represent these values from the ground up.

That is how they’re going to win your business, because it’s not just about a transaction – it’s not just about quality. It is about that human touch, essentially.”

Dana Denis-Smith told the roundtable: “When you start a new business, you have this opportunity to reimagine something. Obviously, I could’ve just built another law firm but I reimagined a legal profession where women were at the table, which is not what I had seen when I was a lawyer at Linklaters. When you’re an entrepreneur, you essentially start a business around a problem and you say, ‘This is broken. I’m fixing it’.”

ETHICS

As indicated earlier, multiple issues have arisen in the last couple of years to raise concern about the standard of the profession’s ethics. Notably, the Law Society’s 2022/23 president, Lubna Shuja, launched a three-year project on ethical standards, highlighting the need to go beyond the strict application of rules to ethical behaviour more broadly.

The society held a series of roundtables with members which she says highlighted areas where the profession wanted more support, such as client selection and onboarding, changing firm culture, ESG issues, and corporate structures and the independence of in-house counsel.

Ms Shuja says workplace culture could be a root cause for unethical behaviour and conduct.” Leadership is key. We must see personal behaviours and virtues across the profession –including at the senior levels – which create an environment that supports, rather than prevents or suppresses, ethical behaviour.

“The culture in any organisation is so important– its openness and propensity to share mistakes, misgivings and learnings, rather than fostering a practice of blame and dismissing concerns.

These all have an important role to play in creating an environment of psychological safety. In short, it is difficult to imagine a workplace in which good ethics thrive unless there is also a healthy and supportive culture built on trust, openness and principled leadership.”

For in-house lawyers, the key ethical question has always been maintaining their independence. Groundbreaking research released by the SRA earlier this year found that in-house lawyers were generally able to withstand pressures but a minority reported demands to act unethically –10% of the 1,200 surveyed said their regulatory obligations had been “compromised”.

A further 5% had faced pressure to “suppressor ignore” information which could conflict with their professional obligations, while the same proportion had experienced “pressure from colleagues not to disclose information that was not in the best interests of the client”.

The SRA said it was concerned that in most teams there were some weaknesses in policies and controls which would help them to oversee and identify risks. “In particular, we noted that balancing regulatory responsibilities and independence while safeguarding effective working relationships could be challenging. These challenges may be exacerbated if in-house teams have limited resources and a lack of focus on ethics in day-to-day learning and work activities.”

More than a third (36%) of in-house lawyers said they had explained to their employer that in certain circumstances their ethical duties outweighed their duty to them, but almost all said they would feel comfortable saying ‘no’ if asked to advise on a course of action that was unethical. A quarter of junior in-house lawyers had not received any ethical training.

Not all in-house lawyers were impressed by the research, with a group publishing a response which disagreed with the comments of SRA chief executive Paul Philip that only a minority of in-house lawyers were struggling. “It is common for in-house lawyers to face ethical challenges and pressure to compromise their regulatory obligations. This is not a minority issue. To conclude otherwise indicates underreporting, undue optimism and or other deficiencies in the review.”

The review’s “optimistic tenor” was also inconsistent with statements within it, they said, such as the comment that “many in-house solicitors described experiencing commercial and political pressures and professional isolation”.

They called for the SRA to issue more guidance, to reach out to the chief executives and boards of employers to outline the regulatory requirements of in-house solicitors, and require that a summary of professional duties should be included in in-house lawyers’ employment terms.

Paying it forward

It is, of course, nonsense to suggest that all younger lawyers are, or should be, motivated solely by higher ideals and should only be engaged in legal work with a social justice or similar purpose. Just on a practical level, the salaries on offer in the City are obviously attractive to those weighed down by student debt.

At the same time, the notion of ‘paying it forward’ from being in a privileged profession is strong. Lara Oseni said she moved to the General Pharmaceutical Council because of what it offered her personally in terms of career progression. But she is now thinking about what she can give back to the profession. “How am I sending the elevator back down to others who are trying to enter the profession, who, maybe like me, might have had to overcome certain barriers?”

She continues: “I now think that the place I work shouldn’t just be somewhere I get a paycheque from. I want to be doing something in my daily work that is benefiting junior legal professionals and the organisation/firm I work for, for generations to come. As a previous chair for the inclusion network at my workplace, it felt rewarding being able to be a part of positive organisational change. This then encouraged me to want to drive change in the profession more generally and is part of the reason I joined the Law Society’s Junior Solicitors Network.”

Some employers are genuinely committed to ESG but plenty are still paying lip service – almost all of our survey respondents agree that some organisations are guilty of window dressing when it comes to tackling DEI and other ethical issues. And yet half say their own employer has a purpose beyond profitability.

Either way, they should realise that this generation will continue to push them. Take the law firm celebrating that 33% of its partners are women. “The question I always ask is, ‘What’s next?’, “says Grace Kendrick. “You can’t just leave the conversation at, ‘Congratulations, you’ve reached your target. It’s an ongoing change and you always have to keep pushing for the next big change and thinking about what you want to do next.”

Holly Moore agrees. “I don’t think anyone at any level can get complacent and be like, ‘Okay, we’ve reached 33%’, or whatever your figure is.

Now, aim for 35%, 40%, 50% – and why are we not just aiming overall to be better?

Maybe lawyers are focused on numbers and statistics, just to show everyone else, but why are we not just aiming for the bigger picture.

As soon as I finished my apprenticeship, I was in touch with HR, with directors, saying, ‘Why have we not hired anyone else? Let’s do it.’ We’ve now got two more solicitor apprentices and we’ve got some employees internally doing the SQE, which is great but, again, that’s a small change in a massive pond. So it takes a lot of people to make the change.“

“The ‘What’s next?’ question is such a good one because there’s so many facets that make up ethics, purpose and values,” adds Abigail Pidgen. “If a company says, ‘Look, we had 2% female partners and now we have 33%, look how great we are’, then we have to ask, what’s your social mobility metric? What’s your accessibility for disabled lawyers? There are so many different things that you need to be doing well in and need to doing better at. You should not mask other areas that you’re failing in with the one area you’re doing well in.”

For Priya Dasani, the growing numbers of people from diverse backgrounds will have a snowball effect. “I’m hoping it’s going to be a slow change that suddenly quickens, because when we get people in those positions of power, and it might take a bit of time to get them there, then all of that change from then on will be pushed forward.”

“Legal businesses that reflect the core principles of purpose, equality and environmental awareness will be the trusted partners of clients.”

DANA DENIS-SMITH

CEO, Obelisk Support

Reshaping the Legal Ecosystem

The world is changing. There is growing dissatisfaction with maximising profit as the driving force behind economic activity.

B Corps, employee-owned businesses (a small but growing trend in the law) and others are starting to push back and look for another way. Whether running law firms or advising companies in-house, lawyers are central to making this work.

This can seem antithetical to the traditional partnership model, where short-term profits per partner are the focus, but the movement to embed new principles into the practice of law and management of legal practices is growing. Clients, mindful of their own responsibilities, are pressing for their supply chains to reflect these new priorities. The legal equivalent of ‘Nobody ever got fired for hiring IBM’ is under threat –what an organisation stands for is becoming a starting point. With so much fresh thinking in the market, there will be less reverence for the established institutions.

Some law firms are embracing this, while legal business such as Obelisk Support are driving change, providing businesses with modern trusted partners, and lawyers with employment options they have never had before.

Businesses are now in an era of ‘show, not tell’ and law firms are not immune from scrutiny. It is not enough to draft the policies and send out the press releases – they have to prove they mean something. When told proudly about a firm’s parental leave policy, a visiting general counsel we know of demanded to be taken round the office there and then and introduced to those who had actually taken advantage of it. Could you meet a challenge like that?

What are your values? Everyone has them but law firms have been slow to explore and express them. What does the next generation of partners want to inherit? Succession is more than just a TV programme.

We envisage that the law firm of the future will be values-driven in a way that supports diversity in its many forms and creates the platform for motivated staff to deliver for their clients. Obelisk Support was founded on the principle of #HumanFirst and we have never had reason to doubt the path this has taken us down, of which B Corp certification is the latest manifestation.

In-house teams are embracing this too, both by looking at what they can do internally and also using their buying power to demand and reward law firms that see how the world is changing.

Some of the gains have come about by chance, pandemic-led flexible working being the most obvious. Do not throw these away because of how they happened – flexible working is a core facet of DEI.

It’s not going to happen as quickly as many hope but the barriers are coming down. PEP will still be the metric that many law firm partners look at first. It has been suggested that PEP should be recast as people, environment and purpose. Weare on the way.

About Obelisk Support

Obelisk Support is a B Corp Certified ™ business with a clear social-impact mission: to keep outstanding legal talent in the law.

The home of flexible legal work, we have over a decade of experience delivering flexible legal support and are unique in our expertise to help legal teams and law firms boost capacity in a cost effective and agile way.

Founded on the principle of #HumanFirst, we connect great businesses with pre-vetted, high quality, flexible legal support powered by our pool of experienced, mostly City-trained lawyers and best-in-class paralegals who want to work differently. What sets us apart is our commitment to keeping first-rate legal talent – often excluded by traditional practice due to caring commitments, age, or background – working in the law.

Through our multi award-winning business model, our legal consultants can act an extension of your team within a matter of days – or even hours. Partner with us to deliver strategic impact, stay agile, manage your costs effectively and enrich the diversity of your supplier base – plus you’re championing flexible legal work that’s great for your business and improving diversity and inclusion in the legal profession.

Methodology

This report is based on a multifaceted methodology which includes conducting our own survey of junior lawyers, interviews with key figures in the profession and a roundtable discussion at which a vibrant mix of junior lawyers had their say on these issues. In addition, we carried out an extensive review of existing research.